As a faculty developer in higher education, I thought I was aware of most of the issues and questions surrounding AI in education, but the UNESCO’s new paper about the topic still held some surprises for me.

The paper, written by UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Education Stefania Giannini and published on July 3rd 2023, takes a thorough look at how humanity, and education systems in particular, are dealing with AI. It also has some stern suggestions for schools and society at large. Here’s a summary of the paper, along with my thoughts about what we instructors can actually do about all these issues.

Same old, same old? How AI is an issue we’ve seen before

The UNESCO paper highlights the ways in which AI worsens many issues that we’re already grappling with.

Monopoly. Giannini reminds us that it’s not a good idea to only have one or two AI platforms hold a near-monopoly on our knowledge systems. It’s always been problematic when one information technology provider has had the power to influence how humans create, process, and store information. Just as we humans are diverse, we need diversity in our knowledge systems.

Proprietary. AI tools aren’t created by people with society’s best interests at heart; they’re created by people operating within a capitalist system (Giannini doesn’t actually use this term) who want to make profit. We shouldn’t expect AI tool creators to regulate themselves – it’s a conflict of interest for them.

Digital inequality. This issue is already on the World Economic Forum’s list of global risks that will only get more problematic in the future. PCs, Internet connectivity, and smartphones, as well as the education needed to use them mindfully and safely, are not distributed equally. The more advanced our digital tools become, the worse digital inequality becomes – including in education. Some schools on our planet are literally struggling to keep the lights on, while others give every student a free tablet. Even in Western countries, students have a lot of inequality in their access to devices and the Internet, as we saw during the pandemic.

Displacing humans. All humans have 24 hours in the day, all humans have limited cognitive resources. The more space technology takes up in our lives, the more human interaction is displaced. Giannini reminds us that many young people spend more time online than offline, and that during the pandemic we saw how education suffered when everything had to be online. A flexible mix of online and offline interactions is good for education, but we should never forget the value of human interaction.

Influencing. Young people, especially, are susceptible to being influenced by others. We’ve already seen how social media self-optimized for engagement, meaning that its algorithms became better and better at hijacking young people’s emotions to keep them hooked to their screens. And this was just via feeds of content. An actual chatbot posing as a friend will probably have a much easier time influencing people, and in much more nuanced ways.

What’s new? Why AI is an unprecedented development

As the previous list shows, humanity already has enough problems with technology. But unfortunately, AI adds new issues to the mix as well.

What’s in the box? Giannini reminds us that not even AI developers know exactly what it’s doing or what it’s capable of. One might argue that social media algorithms began this trend, but AI is definitely a much larger and darker black box than anything we’ve ever seen before. This means that…

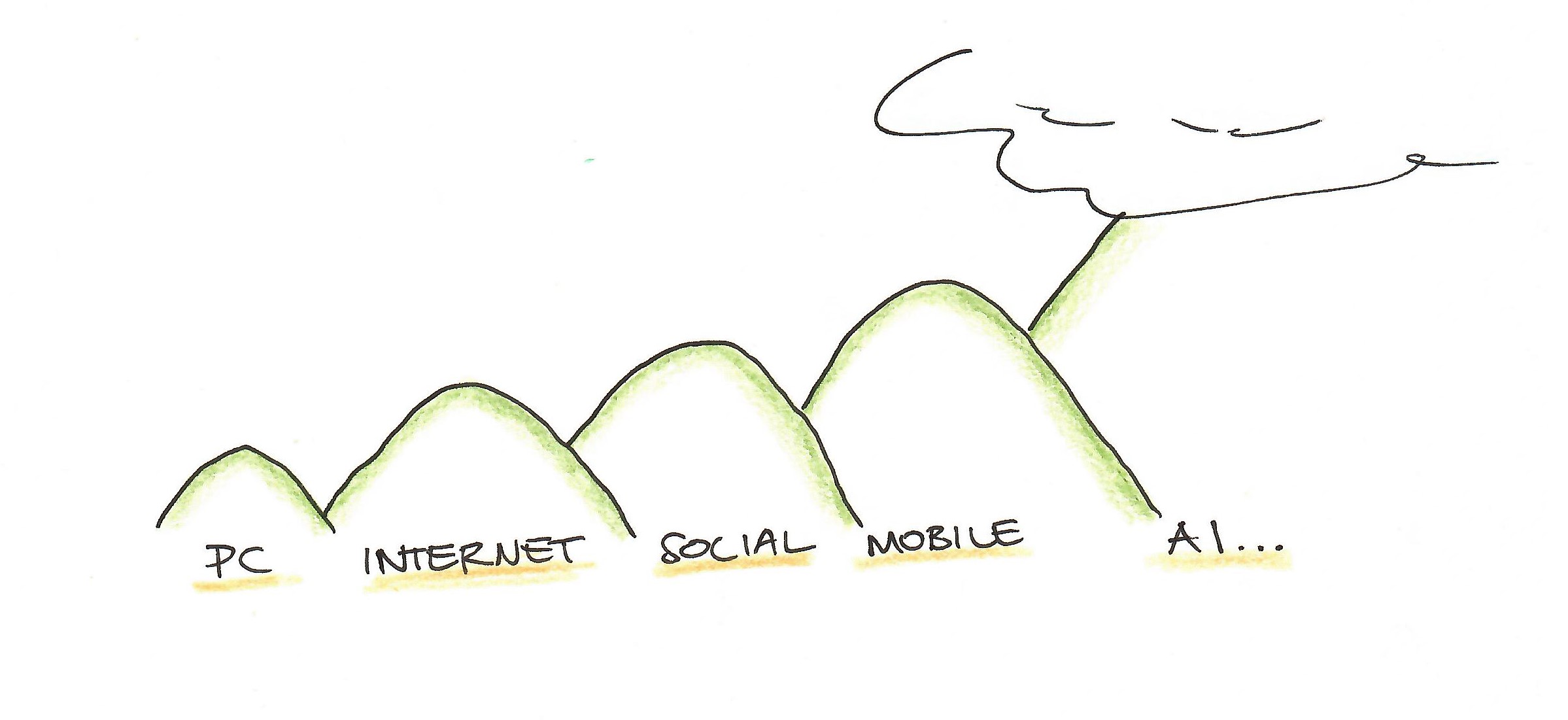

We don’t know what’s coming. Giannini has lived through multiple digital revolutions: the rise of personal computers, of the Internet, of social media, and of mobile devices. The AI revolution, she says, might make the others look minor in comparison. We might be nearing the creation of an artificial general intelligence, a true AI in the original sense – a sapient machine. This is not only scary in and of itself, but it also means the usual paradigm of education is broken. Giannini argues that education usually follows the following paradigms:

- We know what the world is like.

- We will prepare people to thrive in this known world.

But if we are fundamentally unable to predict what is coming, then we don’t know what to prepare for. There is no “known world” anymore.

We’ve had four digital revolutions, but AI might be the biggest one yet. Sketch by Nina Bach.

We’ve had four digital revolutions, but AI might be the biggest one yet. Sketch by Nina Bach.

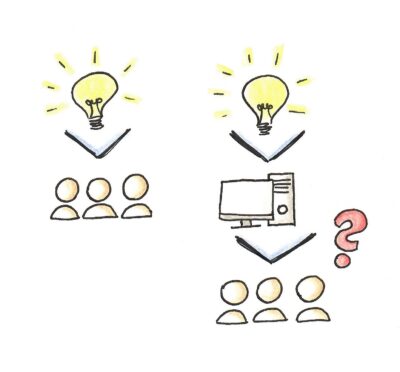

Opportunity cost. For the first time ever, we have a potential new target group for education: machines. (This is one point that I never thought of and thus found highly interesting.) Throughout human history, we’ve targeted education at other humans. We want humans to learn. We want humans to thrive in the world.

But now we can also invest time, energy, people – all kinds of resources – into educating machines.

Will the future paradigm change from “humans educate humans” to “humans educate machines in the hopes that those will then effectively educate humans”? Giannini reminds us that educating humans should remain the most important goal. Every dollar we invest into optimizing AI tools is a dollar we didn’t invest in a human teacher or human school – this is the so-called opportunity cost. Every time you do something, you’re not doing something else.

What to do? The UNESCO’s answer

Problems and issues abound. What does the UNESCO recommend we do about them?

Slow it down. Giannini joins the many, many experts calling for a slower pace in AI. However, she wants schools and universities to take responsibility for this, as corporations will have a conflict of interest in slowing down their own product development (see “Proprietary”, above). Giannini recommends taking as much care with bringing AI into schools as with developing new textbooks.

Prioritize humans. The UNESCO remains firmly pro-human: “Education is – and should remain – a deeply human act rooted in social interaction.” (Giannini, 2023, p. 7)

Giannini sees human teachers as the “main ingredients” of education. Automation of education should not be seen as a fix for education inequality.

Vet AI for safety. Giannini calls on schools and universities to vet AI for safety, just as textbooks are vetted for safety. The slower pace also comes into play here, as developing systems for vetting AI tools will take time. We also need more AI experts working for the government in order to help vet AI – less than one percent of AI PhDs go on to work in government after graduating.

Reflect. AI creates two wider areas of uncertainty:

- What kind of AI can and should humanity develop?

- What should we do in education – and how and why should we do it?

Yes, AI poses a question in and of itself – what do we want it to do, who should use it, etc. – but because AI has removed the so-called “known world” (see above), education itself is being called into question. Giannini wants educators to use this moment to reflect, not how to teach using AI, but what teaching is for anyway. Basically, the essential aspects of education – who is educating whom, to what goal – are all being torn down by AI.

When we shift from teaching humans to teaching machines to teach humans, new questions arise. Sketch by Nina Bach.

The UNESCO paper: My review

In my view, this paper is a good summary of the broader issues surrounding AI. It’s only eight pages long, yet manages to present a broad range of ideas. While Giannini recommends that educators remain “open and optimistic”, most of her points are cautionary. Many of her arguments are familiar to anyone who’s been following the discussion about AI; still, she does present one or two ideas I hadn’t encountered yet.

Personally, I’m glad to see the UNESCO taking such a cautionary stance. But as so often with papers like this, after reading I’m still left with the question…

But what can we really do?

Sweeping statements and grand ideas about what humanity should do are all well and good. But what can we instructors do in daily life in the meantime?

Here are some ideas.

Awareness and reflection. We should be aware of all the aforementioned big questions:

- What kind of AI can and should humanity develop?

- What should we do in education – and how and why should we do it?

They are still unanswered, and there won’t be easy answers anytime soon. Sitting with this uncertainty is uncomfortable, but the only wise option. Consuming news about AI is important in order to stay informed, but we should remain critical. Just because someone says the world is heading in a certain direction doesn’t mean it’s true. We should be aware of what we know and don’t know, but also reflect on these questions, especially the second one about education, and form preliminary opinions.

Values can be helpful here: AI is rapidly changing the world, but our personal values don’t change, or at least not as quickly. Schwartz’s theory of basic values can help us reflect on our values and form opinions about the meaning of education in a changing world.

Self-care. Because being aware of large, unsolved issues is psychologically taxing – our brains like certainty and easy, energy-saving facts – I think that self-care is more important for instructors than ever.

- Practices that bring us to the present moment and restore our energy, like exercise, taking a walk, meditation, journaling, yoga etc. can ground us and keep us calm in the face of an ambiguous future.

- Escapism has its benefits. While escaping can serve self-suppression, or pushing away uncomfortable thoughts and sensations, it can also be a good tool for self-expansion: experiencing something pleasant and discovering new ideas and new aspects of oneself. I’ve been reading lots of sci-fi recently, and I find escaping into other universes where AI has already developed into humanity’s friend or foe relaxing and inspiring.

- Have boundaries around your teaching and news consumption. Give your brain a break – experiencing detachment from work is an essential part of recovery. Make sure to take breaks, evenings off, and days off if you can.

Take a bit of action. After reflecting on the meaning of education (in accordance with our values) and practicing self-care, it’s time to take action. As instructors, we want to reach those pesky formal learning goals that might be part of an antiquated system, but that we are still commited to; yet we may also want to infuse our teaching with a modern mindset that will prepare students for the unknown world ahead.

There are small steps that can make this happen. Again, boundaries are important. It’s not realistic or necessary to completely change the way we teach. But here are some concrete ideas for our teaching:

- Activate students. Lecture a little less and have students do a little more. Tasks can include working with AI, or reflecting about AI and how it relates to the topic. This raises AI literacy and gives education more meaning. It’s high time to become a “guide on the side” who supports students as they work on tasks instead of staying a “sage on the stage” who lectures students while they sit there and listen.

- Flip the classroom. If there’s no time in class to activate students, but we’re giving them homework or leaving them to prepare for exams on their own, flip the classroom! Have students work through tasks at home and then discuss their progress and questions in class. Even a small step of shifting ten minutes of lecture time to self-study, thus freeing up ten minutes of discussion time in class, can change the dynamic in the classroom. A PowerPoint presentation can already be replaced by a video, and may someday be replaced by AI. But actually talking to students about their progress is where human instructors are very valuable.

- Rethink learning goals. If we feel like there’s no time to foster students’ AI literacy, study skills or similar, then maybe it’s time for a strategic approach. If we cut some topics from our class, but use that time in order to empower students to develop study skills, AI literacy, and other skills, then they will be able to research those topics for themselves some day. We can’t assume that we know exactly what content students will need in the future anymore. And there is more content than can ever be taught, anyway. Time spent honing “future skills” and media and AI literacy, however, is always well-spent.

We at Hochschuldidaktik Online are working on a course (in German) about how instructors can promote students’ AI literacy. You can sign up for our newsletter if you want to be notified when it’s published. And we already have a course in English about how to teach in a world with AI, with many more ideas for small things we can implement in our teaching.

I hope I have managed to answer the question of what we can actually do in the face of all the issues Giannini mentions in her paper. Do you have any other tips? Have you read the UNESCO paper? What did you think of it? We’d love to hear your thoughts. Because discussions among us humans are still, I think we can all agree, a very meaningful endeavour.

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar